|

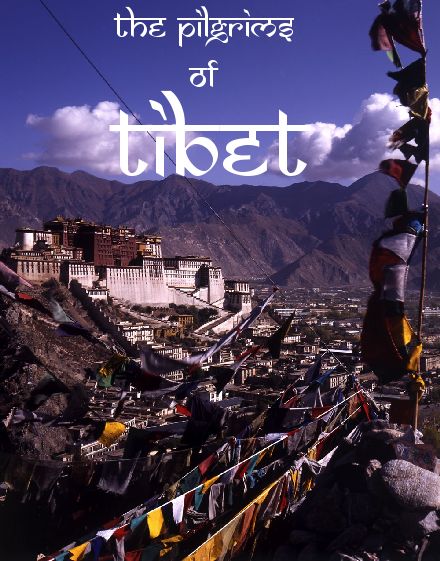

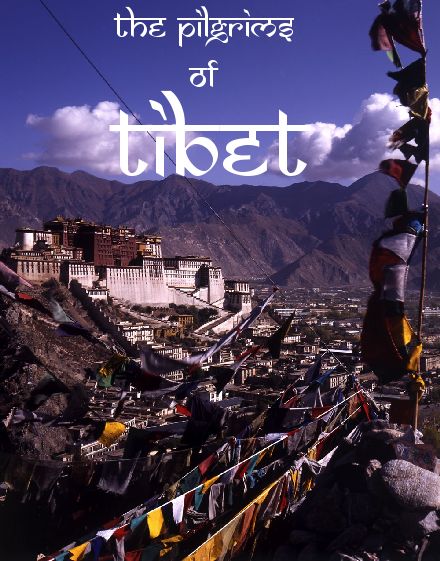

Prayer

flags-blue for the sky, white for clouds, green for grass, yellow for the

earth and red for fire-flutter in the wind throughout Tibet, even in the

most remote and uninviting locations. As pilgrims traverse the country

they leave them tied to piles of rocks or strung together flapping from

makeshift flagpoles on high mountain passes, hilltops and chötens

(shrines erected at important religious sites). They believe that as the

wind brushes across the fabric of the flags the prayers written onto them

are transported to heaven bringing merit to the one who puts them in place.

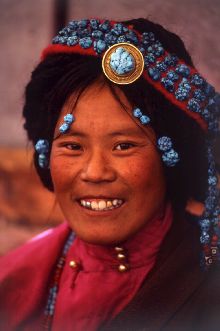

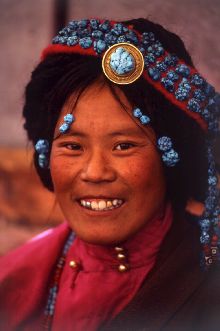

Pilgrimages to the significant

religious sites scattered across the country are central to the lives of

Tibetans. The hardships involved seem incidental. People are prepared to

travel for days on the back of trucks to reach their destinations.

The dust in summer

is choking and during winter the pilgrims endure the bitter cold, biting

winds and freezing temperatures with only their thick yak hair coats to

protect them.

They cross a landscape parched

brown, strewn with rocky rubble and treeless to the horizon. It resembles

an alien place, inhospitable, unprotected, barren and often uninhabited.

In places wild rivers cut

through the moonscape eroding the exposed earth, eating it away and sending

steep hillsides and roadways tumbling into their surging waters.

In other places vehicles

turn the stony bottom of a dry river-bed into a road as they cross a high

plateau but at such an altitude that mountain tops 5 thousand metres high

are at eye level. |

|

Some roads cross vast plains

that expand into the distance where Himalayan peaks sparkle white below

the deep blue of the high altitude sky, and skirt glaciers-jumbled and

mangled chunks of ice the size of houses-which shimmer blue-green in the

sunlight as they slither, imperceptibly, from mountainsides. Lack of oxygen

brings on headaches and mild nausea for travellers not used to the altitude

even though they are sitting quietly on a bus or the back of a truck. |

|

The expense of these journeys

can sometimes leave the pilgrims without enough money to get home. Despite

this, thousands are still prepared to undertake the hardships in order

to gain merit, highlighting one of the most significant aspects of Tibetan

life: the devout, and almost universal, adherence to Tibet’s unique branch

of the Buddhist religion.

Travellers arrive in Lhasa

every day to pay homage at the great monasteries, and temples and visit

the red and white washed Potala Palace, once the home of the spiritual

leader of the Tibetan people. |

From early in the morning pilgrims

climb the steep ramp from street-level into the lower courtyard of the

Potala. They shuffle their way up through the massive labyrinth of half

lit halls, shrines and tombs of past Dalai Lamas in a single file, clutching

the coat of the person in front. Inching down narrow, dark corridors, past

exquisite images of Buddhist deities, up ancient wooden staircases and

into cavernous rooms barely lit by yak butter lamps, pilgrims slowly make

their way to the roof where they are afforded a panoramic view across Lhasa

and the surrounding countryside. |

Young

monks work hard to gain as much knowledge as they can in order to progress

through the various levels of understanding.

|

During

debates held in monasteries across Tibet the monks are tested by their

peers in a frenzied question and answer session that goes on for several

hours.

Surrounded by his colleagues,

question after question is thrown at the young monk. His responses are

met with a shout, a stamp of the questioners foot and an aggressive, single

hand clap over the initiates head signifying if the answer is correct.

The teachers at the monasteries instruct the questioners to "stamp your

feet so hard that the door of hell will be broken open and clap your hands

so loud that the voice of knowledge will frighten the devils all over the

world." |

The twenty-first century arrives

slowly in Tibet. The first motorised transport did not arrive until the

1950's and Buddhist scriptures are still printed one page at a time from

wooden printing blocks. In some senses not much has changed from the days

when pilgrims might have ridden their horses or even walked across Tibet

in their quest to hear for themselves ‘the voice of knowledge’. |

|

PLEASE NOTE:

A wide range of original photographic essays are available for publication and are generally accompanied by a minimum of between 60-80 high quality images shot in high resolution 35mm digital format.

Editors may suggest specific story concepts related to the current schedule of the photographer with no obligation as to the eventual purchase of the material produced.

Barrie Brown Photography

Email: barrie@barriebrown.com

Copyright B. Brown 1999-. All images and text shown here are the exclusive property of Barrie Brown and may not be used, stored, reproduced or redistributed without the express written permission of Barrie Brown or his assigns. |

|