|

||

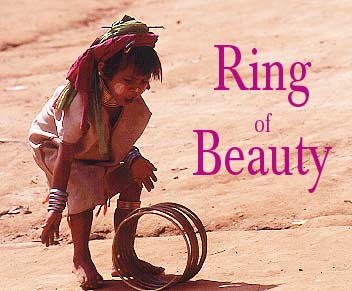

Padaung Long Neck WomenA group of women gather in the shade of a flimsy, earthen-floored structure on the bank of a parched creek that snakes into the village. Their gaze is concentrated on Ma Lai, a small, weather-tanned woman in her mid-thirties, swatches of coloured cloth tied into her hair and her lower arms wrapped in heavy metal bracelets. She is performing a ritual that has made these people famous throughout the world. | ||

| In this isolated jungle encampment near Nai Soi on the Thai-Myanmar border, a forty-minute flight from Chiang Mai in Thailand’s far north, the women continue to practice a tradition that first began in the villages of their home country across the border. | |

Ma Lai hunches over, locks her elbows, and forcefully presses down. Her strong hands skilfully manipulate a large spiral made of brass that stretches to more than seven metres. She bends and twists it until it wraps closely around the neck of Ma Yung, a 14 year old girl who has asked her to replace the 17 cm high neck coil that she removed a week earlier. The women belong to the Padaung tribe and are known around the world as the “giraffe women” of Myanmar because their tradition of wearing a heavy brass coil around the neck gives the impression that their necks are enormously elongated. "The rings are not close enough to each other", she complains and unwraps part of the coil from around the young girl’s neck. |  | |

| The heat from the late afternoon sun penetrates the roof of dried leaves on the small shelter and roasts the still air that hangs in the valley and blankets the cluster of simple, split bamboo houses that occupy the narrow cleft between two steep, jungle-covered hills. Ma Lai sits down to rest and ponder how best to achieve the most beautiful coil. "The rings must be smooth and close together otherwise the coil does not look beautiful", she explains as she buries her face in a small towel to wipe away the perspiration. | |

Ma Lai is aware that her

ability to fashion a beautiful coil is being scrutinised by others in the

village and she is meticulous in her work. "Our mothers didn't ask us, it was our tradition, we all expected that it would happen and we followed the tradition without giving it much thought. Most girls wore the coil in those days-a girl who didn't wear a brass coil was not regarded as beautiful and so all the young girls wanted one." "Girls are not beautiful if they don’t have the coil around their neck," maintains 14 year old Ma Kaou, her head swathed in a blaze of yellow, blue and pink flowers atop delicate layers of lace, as she watches Ma Lai work the brass rod into a narrow coil, flared slightly at each end, around Ma Yung’s neck. "I will never take mine off even though it is sometimes uncomfortable." |  | |

| ||

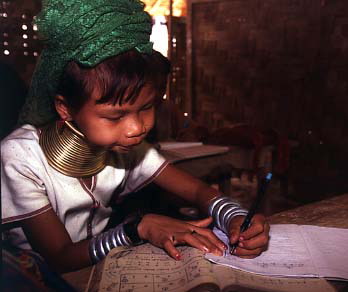

It was discomfort that prompted Ma Yung to remove her coil for what was the third time in the past few years."The coil sometimes makes blisters and it can be very itchy when it is hot,” Ma Yung explains. "I took it off to allow my skin to improve." She originally intended to leave the coil off for about a month but constant teasing by other girls in the village prompted her to put it back after only a week."The skin on my neck is discoloured and still has some blisters that haven’t completely healed,” Ma Yung reveals. "But many of the other girls told me that I am not beautiful without the coil so I don’t want to wait any longer to replace it." Exaggeration, half-truth and misinformation surround the Padaung people and their exotic customs. This story looks at their unique concept of beauty and examines some of the mythology. | ||

The State of PhotojournalismThis point of view (POV) piece was prompted by the amount of misinformation about the Padaung women that exists, even in some extremely reputable newspapers and magazines. The idea, for example, that the neck of Padaung women will break if they remove the ring is just one of these and is totally wrong; the young woman in the picture above, having the ring put back on her neck, happily walked around the village for a week without the coil and the strength evident in her neck muscles posed no risk or danger to her neck. Magazine and newspaper photography covers every topic imaginable. Unfortunately, much of the information that people have about many topics is not backed by the rigorous research and extensive field work that the best photojournalists produce. The reason for this is simple - money. Only National Geographic can afford to send its photographers and photojournalists into the field for extensive periods of time to prepare material for their magazine stories, although NatGeo is also not above inaccurate reporting. In many cases magazines these days are more likely to source material from iStockphoto than commission a photographer to gather material for photo-essays which will run in magazines and newspapers which must now survive on ever decreasing budgets. The downside of this is the quality of the story telling suffers, as it must. Travel stories can be written by someone in an apartment in New Your, Sydney or London much more cheaply than they can be by a photojournalist who actually makes the journey to the place they are writing about and photographing. To establish the authenticity of stories requires the reader to be vigilant about what they are reading. How many times is a conversation reported? How many times is the voice of the people who inhabit the region visited heard in the story? Is it just description and opinion without the voice of the local people ever being heard? These are important questions. And astute readers must demand that magazines and newspapers are producing authentic material that has been properly researched and is not simply some rehash of travel brochures and National Geographic magazines that an author has assimilated. The quality of real photojournalism in the future is going to depend as much on demanding readers as it will on writers and photographers being serious about their work and devoting sufficient time to really learn something significant about the places they visit and the stories they tell.

| ||

| ||